American Thoughts on Australia Day & Acknowledgement of Country

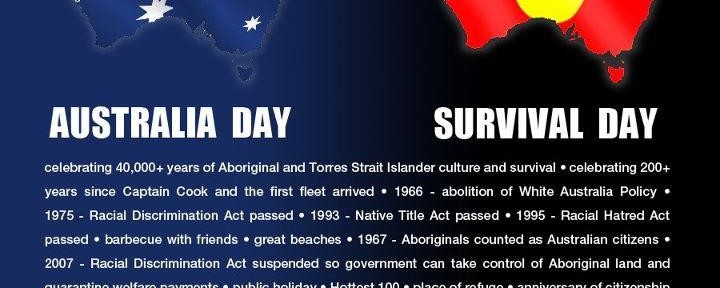

Yesterday/today (the 26th of January; time is a weird thing when you’re straddling the dateline) is Australia Day, also known as Invasian Day—it’s a day of celebration akin to the drunken antics of Americans on the fourth of July for European Australians, “settlers,” and a day of mourning for Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander communities who see it as a day of invasion and subsequent struggle to survive. So basically, the partying of the Fourth of July mixed in with Thanksgiving—after all, the European Australians did much the same to the Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders as Americans did to Native Americans.

White folks, we aren’t so great at respecting other cultures.

Anyhow, you should read this article over at Buzzfeed and watch the embedded video, below. But what I wanted to talk about was something that I saw people doing online: identifying the land they woke up in. This seems to be a variation on the Acknowledgement of Country that happens at a lot of official events, and it’s one where individuals, yesterday, were acknowledging the historic people of the land they live on:

@AnitaHeiss I woke up in Philadelphia, but have lived on Wurundjeri, Ngunnawal, Eora, Butchulla, and Noongar land.

— Nicholas Evans (@neva9257) January 25, 2016

This, I thought, was neat, and a way of showing respect to people who you yourself may not have harmed, but your ancestors did harm, by virtue of their participation in the forming of the place called Australia—or America.

I thought I’d compile my own list of the Native American lands I’ve lived on in my time floating across the United States; what I didn’t imagine was that it would take me several hours to track this information down. After all, I grew up attending Ohlone events in the San Francisco Bay Area, and doesn’t everyone know that the Duwamish were the historical peoples in the Greater Seattle area?

Except that the Ohlone, formerly the Costanoans, didn’t view themselves as a single “Indian tribe” but a loose group of about 50 distinct landholding tribes or bands who shared a similar language, religion, and culture but saw themselves as distinct. They, like many other Native peoples, were squished together into readily identified tribal groups by the United States government during its long period of sucking, and trying to find out the specifics of the folks who lived in a specific area rather than the region (so I coul answer the equivalent of “Philadelphia” instead of “the mid-Atlanic”) proved…frustrating. A lot of this is because by the time anyone in America had the idea that maybe they should record this information, the people were dying or dead; many of the last speakers of languages, the last of their group, tribe, people, were dying in the late 1800s to 1920s, and American society was set on eradication of tribal groups. The disappearance of this knowledge was just fine with most.

So it is with some struggle and uncertainty that I can say I have lived on the lands of the following people:

The Muwekema Ohlone (Alson, Seunen, Luecha, and Puichon)

The Numa, Washeshu and Newe People

The Kalapuyan Peoples (Chelamela and Tualatin)

The Multnomah People

The Duwamish Tribe (Skagit-Nisqually/Lushootseed)

The Iroquois League/Haudenosaunee (Mohawk Nation)

And this morning, I woke up on Lenni Lenape (Unami dialect) land.

I don’t really have anything quippy to say here in finish. I think that the way we—Americans and Australians—handle our commemoration of events is painfully white and alienating, that we casually erase history with no thought to the pain it causes people who call that history their own. I think that it’s a shame we have to repeatedly have conversations about whether or not it’s a problem to have sportsball teams named after racist slurs, that we set up parties on days of massacres, that we celebrate the slaughter of millions with mattress sales and BBQs, and that we can’t get it around our heads to treat the other folks we live with, folks of colour, with the respect we want for ourselves every day.

Knowing the names of the tribal lands I have lived on won’t change any of that, but at least it allows me to move a bit closer to an ideal of mindfulness and respect that I think we should all strive towards.